News

Poll: Do Russians want a ceasefire with Ukraine? Why is Shoigu hated? Who’s to blame for rising prices?

In our previous video, we talked about how anxiety levels among Russians rose throughout 2024, and how the overwhelming majority of people said they would choose any kind of peace over another wave of military draft. All of those surveys now feel like they belonged to a different life—one where peace wasn’t even part of the conversation.

But on January 20, 2025, the world changed dramatically. Donald Trump became the 47th President of the United States and immediately began working to deliver on one of his campaign promises: to broker peace between Russia and Ukraine. We’re not going to discuss here whether that’s even possible. What we’re interested in, as sociologists, is something else: how society perceives the actions of politicians and how people respond to them.

Today, we’re going to share the results of our two most recent surveys. One was conducted at the end of January and beginning of February 2025, right after Trump’s inauguration. The other was done in March. These were telephone surveys of Russian citizens aged 18 and over, each with a representative sample of 1,000 respondents.

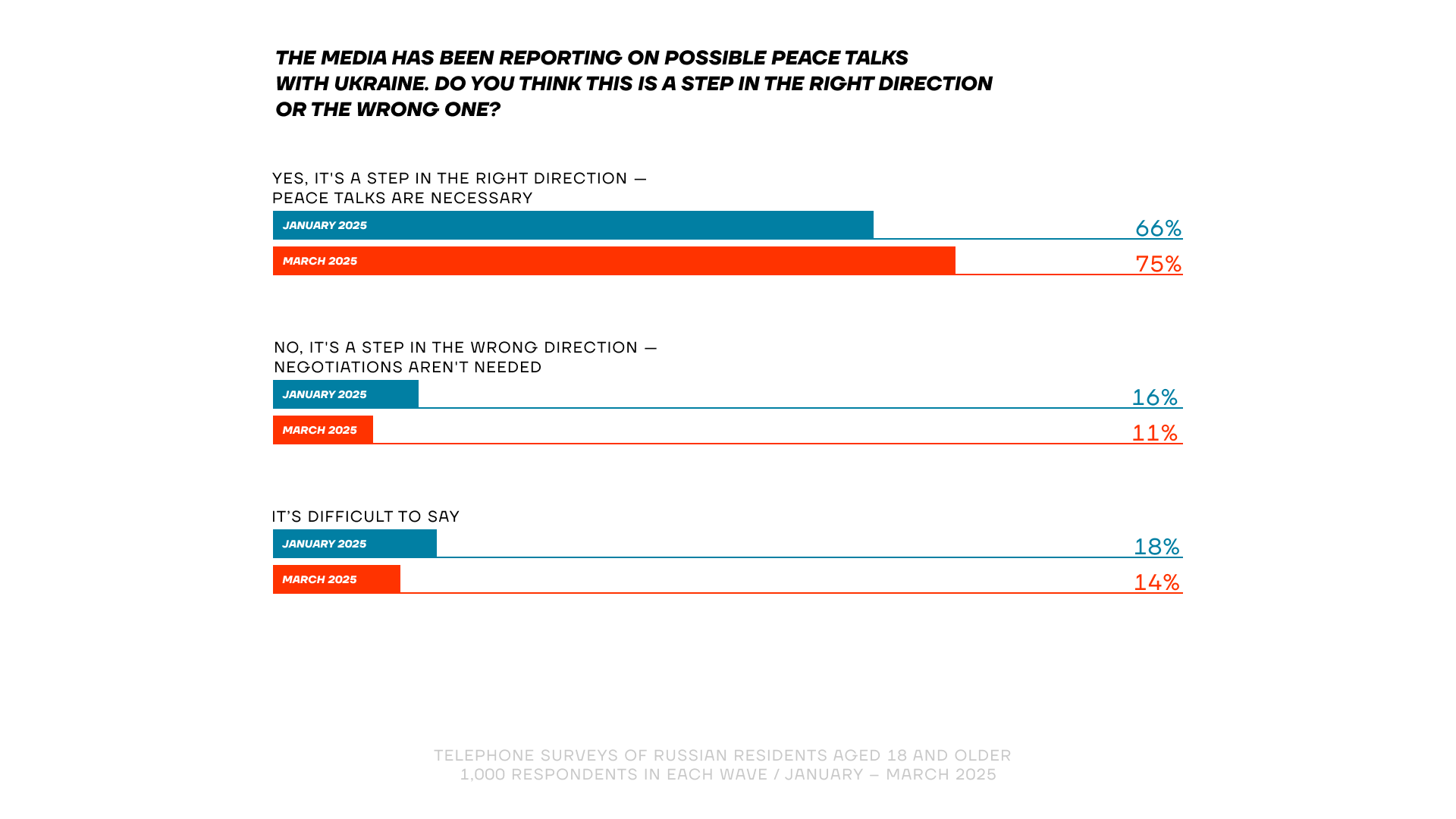

Over the past two months, there’s been a noticeable shift in how Russians view the idea of peace talks. Back in January, about two-thirds of respondents supported them. By March, that number had climbed to three-quarters—a nearly 10-point increase. At the same time, the number of people who see peace negotiations as a step in the wrong direction dropped by a third. And the number of undecided respondents also shrank—which isn’t surprising, given how much space the topic has taken up in the media. People have started to form clear opinions.

And those opinions are overwhelmingly in favor of peace. Today, support for negotiations outnumbers support for continuing the war by a factor of seven. That’s where public sentiment in Russia stands right now—and it’s not the kind of news Putin wants to hear. He has no intention of ending the war. But he’s still forced to talk about peace and put on a show of being open to negotiations—because the Kremlin knows full well that the vast majority of Russians want it.

So, while he keeps launching deadly missile strikes on Ukrainian cities with one hand, he sends envoys to the U.S. and Saudi Arabia with the other. It’s a performance—a lesson in how to fake diplomacy when you have no real interest in it.

It’s clear that most Russians don’t want to keep fighting. But what does “peace” mean to them? Does it mean holding on to illegally seized territory? And if so—what kind of peace is that, really? Let’s take a closer look.

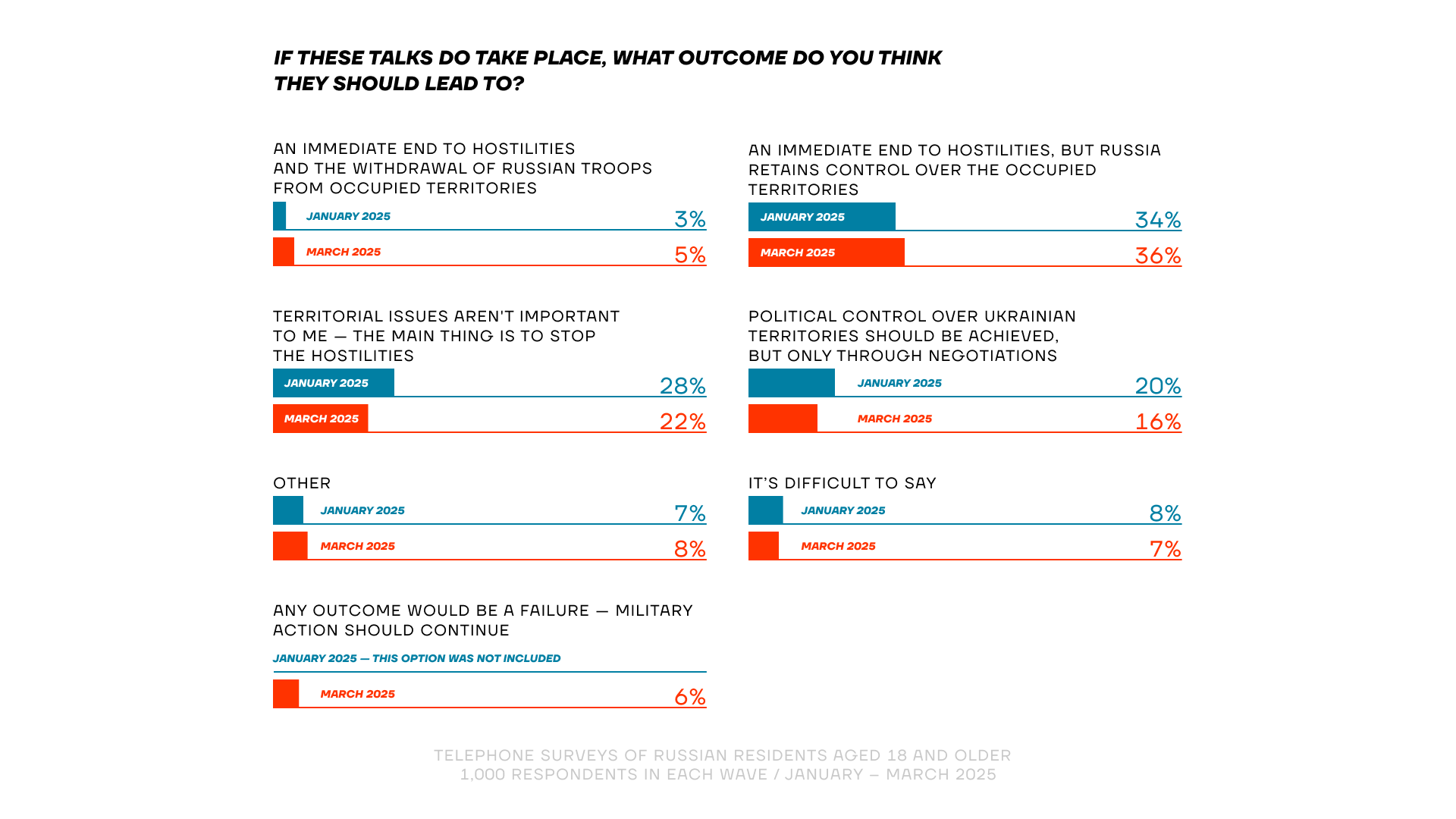

At first glance, it might look that way. The tallest bar on this chart shows the most popular response: support for holding on to the territories Russia has already occupied. But take a closer look.

Because this is such a sensitive topic, we offered a range of response options—ones that allowed people to avoid giving answers that might feel risky or uncomfortable. Only 5% of respondents were willing to say directly, over the phone, that Russian troops should withdraw from the occupied territories. But another 22% said the issue of territory wasn’t important to them—what mattered most was ending the fighting. Another 16% chose the response that conflict should be resolved through political and diplomatic means.

It’s hard to see these people as aggressive imperialists. Add in the 15% who either answered “Other” or said they didn’t know, and the picture becomes clearer: for a large part of the population, the question of borders isn’t the priority. What matters to them is stopping the war—and soon. That group, the peace-first camp, is the majority.

You can see this even more clearly in the March poll, where we introduced a new option that hadn’t been included in January: “Any outcome of negotiations would be a failure—military action must continue.” Only 6% of people chose it.

And yet, this is the one opinion that dominates the so-called “patriotic” blogosphere. Z-bloggers are constantly up in arms about the possibility of a “shady peace deal,” which they paint as the worst possible outcome. They call for marching on Kyiv, taking Odesa, even pushing all the way to the Polish border—we see these demands thrown at Putin daily in that corner of the internet.

But out in the real world? That kind of thinking barely exists. Because the Z-blogosphere isn’t real life. It’s an echo chamber—a fringe space for the most radical 6%, a tiny group of bloodthirsty armchair warriors who bought into Putin’s propaganda and still believe in his fantasy war.

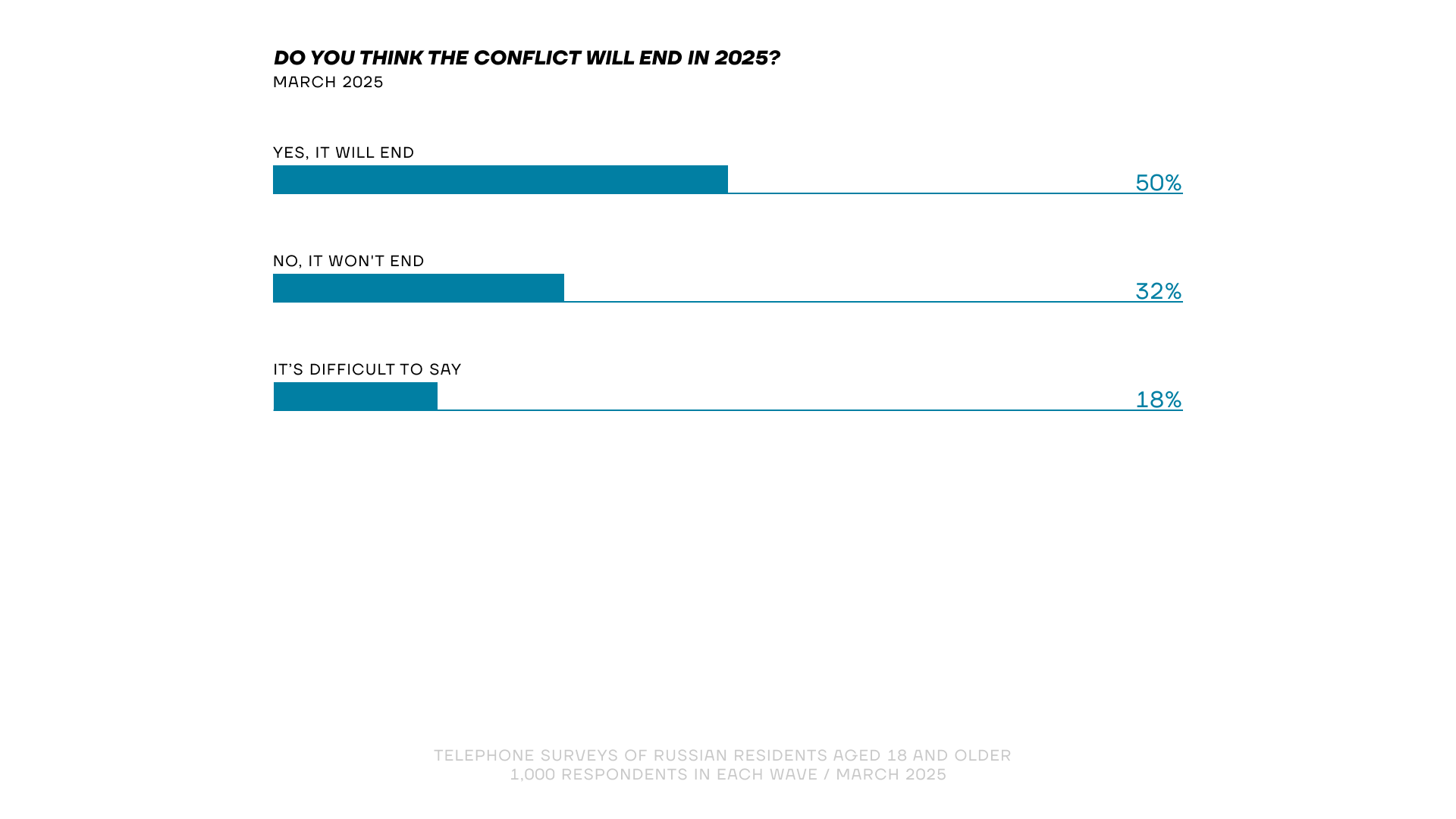

Half of those we surveyed in March believe the war will end this year. That’s an incredibly optimistic view—and one that’s unlikely to survive contact with reality. Politically, it presents a real risk: if peace talks collapse and the war continues, all these people will be frustrated and angry with whoever they believe is responsible. That could become a serious political challenge for the Kremlin.

But there’s another finding that truly surprised us.

If you asked any random person on the street in Russia, “Who’s our biggest enemy?” most would probably say, “America.” Sanctions? Blame the Americans. A Roscosmos rocket fails? It must be America’s fault. It feels like there’s nothing more constant in Russian public opinion than anti-American sentiment—something deeply rooted since the Cold War, if not earlier.

But here’s the striking part: today, the desire to end the war is even stronger than the long-standing hatred toward our main geopolitical rival.

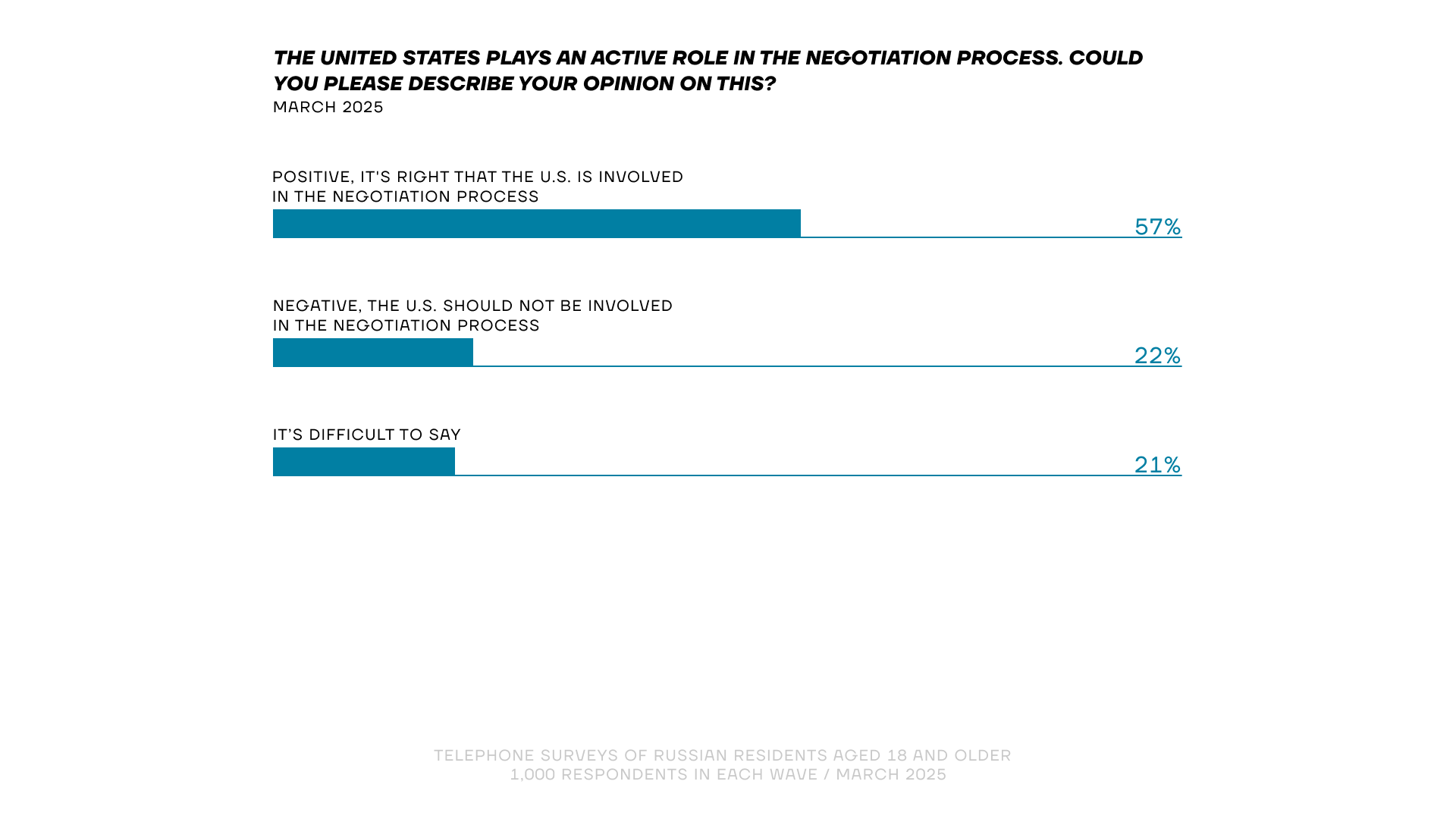

People want peace so badly that 57% say they support U.S. involvement in the peace process. In plain terms, they’re saying: if Putin can’t stop the war he started, we’ll be grateful to anyone who tries to do it for him—even if it’s the Americans, even if it’s the devil himself.

We’re witnessing, in real time, the breakdown of one of the core beliefs that has defined Russian identity for generations.

To test this shift, we decided to shake things up a bit. Every one of our surveys includes a section tracking public sentiment toward politicians. For many years, we’ve only included Russian politicians—which makes sense, since we’re polling Russian voters.

But in March 2025, for the first time in twelve years, we added a foreigner to the list: Donald Trump.

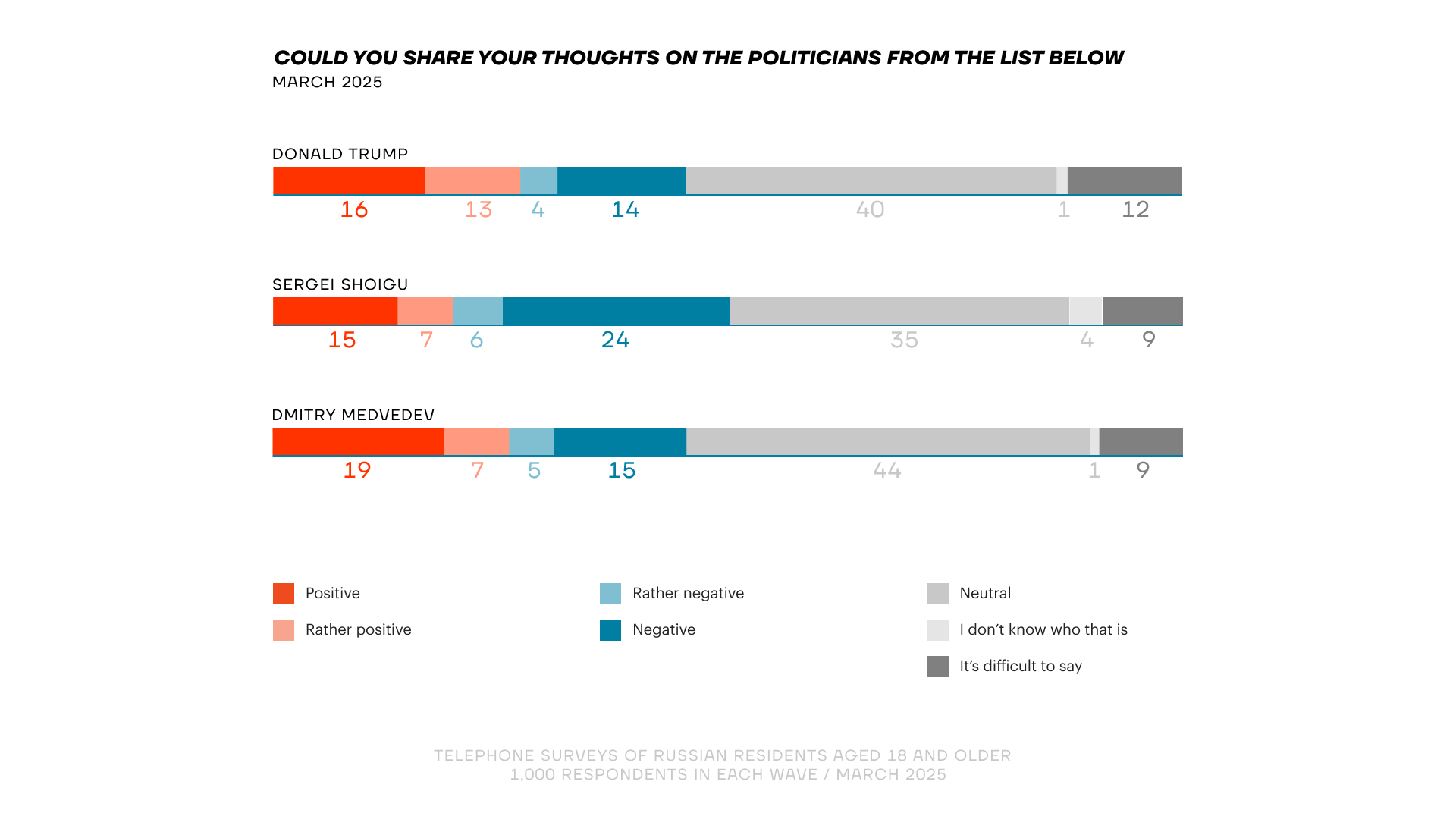

And what a debut! Trump scored a 29% approval rating and an 18% disapproval rating. That’s better than, say, Sergei Shoigu—who got only 22% approval and 30% disapproval. Not long ago, Shoigu was the second-most popular politician in Russia, just behind Putin.

In fact, if there were somehow a presidential race between Donald Trump and Dmitry Medvedev in Russia, Trump would win.

This tells us something important: for many Russians, ending the war is such a high priority that they’re willing to welcome peace—even if it comes from America. That presents political difficulties for Putin, but it also points us in a clear direction:

Through every available channel—livestreams, social media, conversations in break rooms—we need to talk about how Putin is dodging negotiations, derailing peace talks, making absurd demands, and breaking promises.

This topic is safe to discuss, and for the overwhelming number of Russians who want peace, it’s a powerful truth—one that could shift how many of them see Putin.

And we’re already seeing that shift. The second part of our recent research focused on economics. We’re not just asking about politics—we want to understand what daily life is like. And right now, the answer is: unstable, and getting worse.

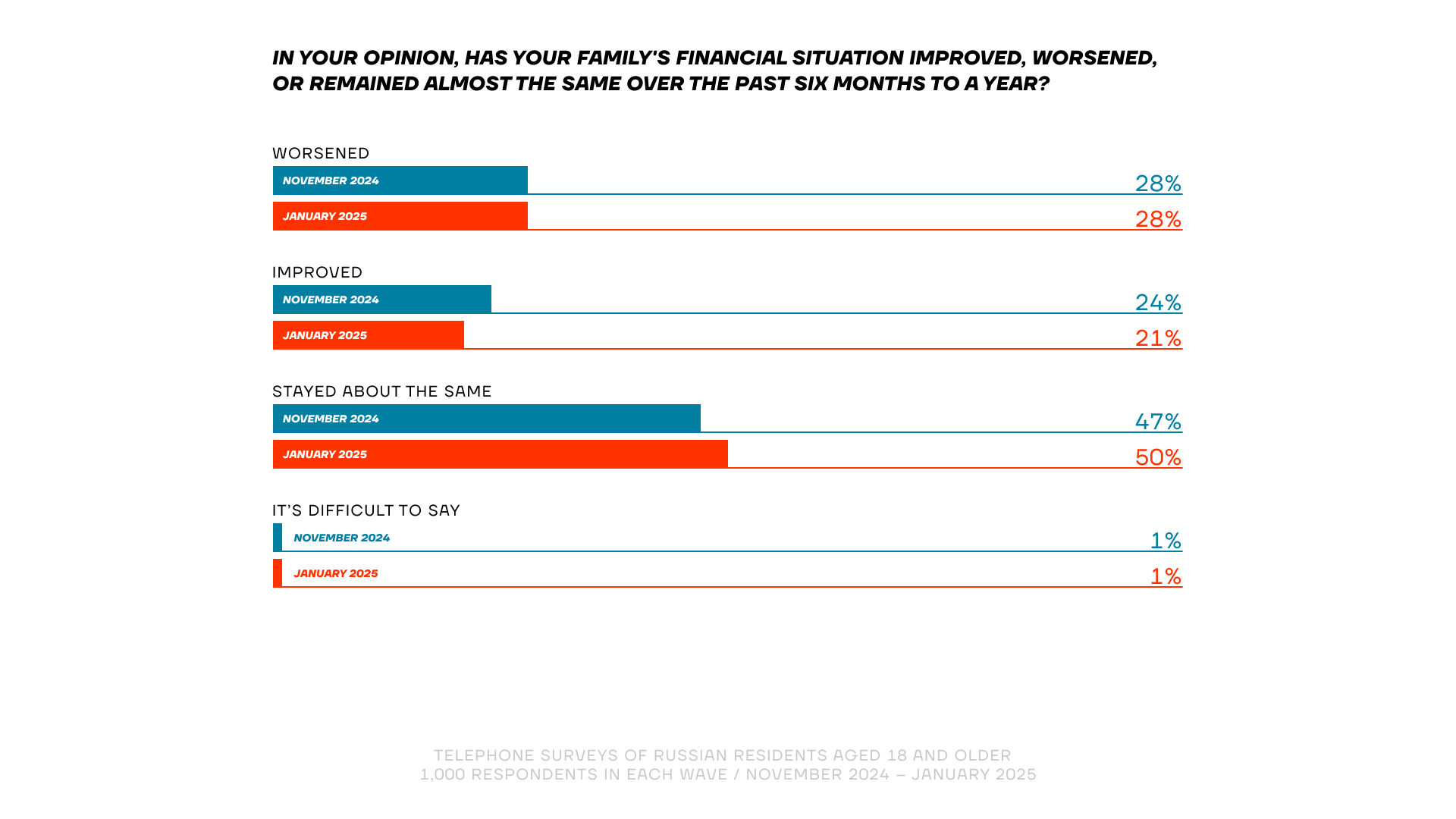

The number of people who say their family’s financial situation has improved is shrinking. Just 21%—barely one in five—report any improvement. Meanwhile, 28% say things have gotten worse, and they’re struggling more than before.

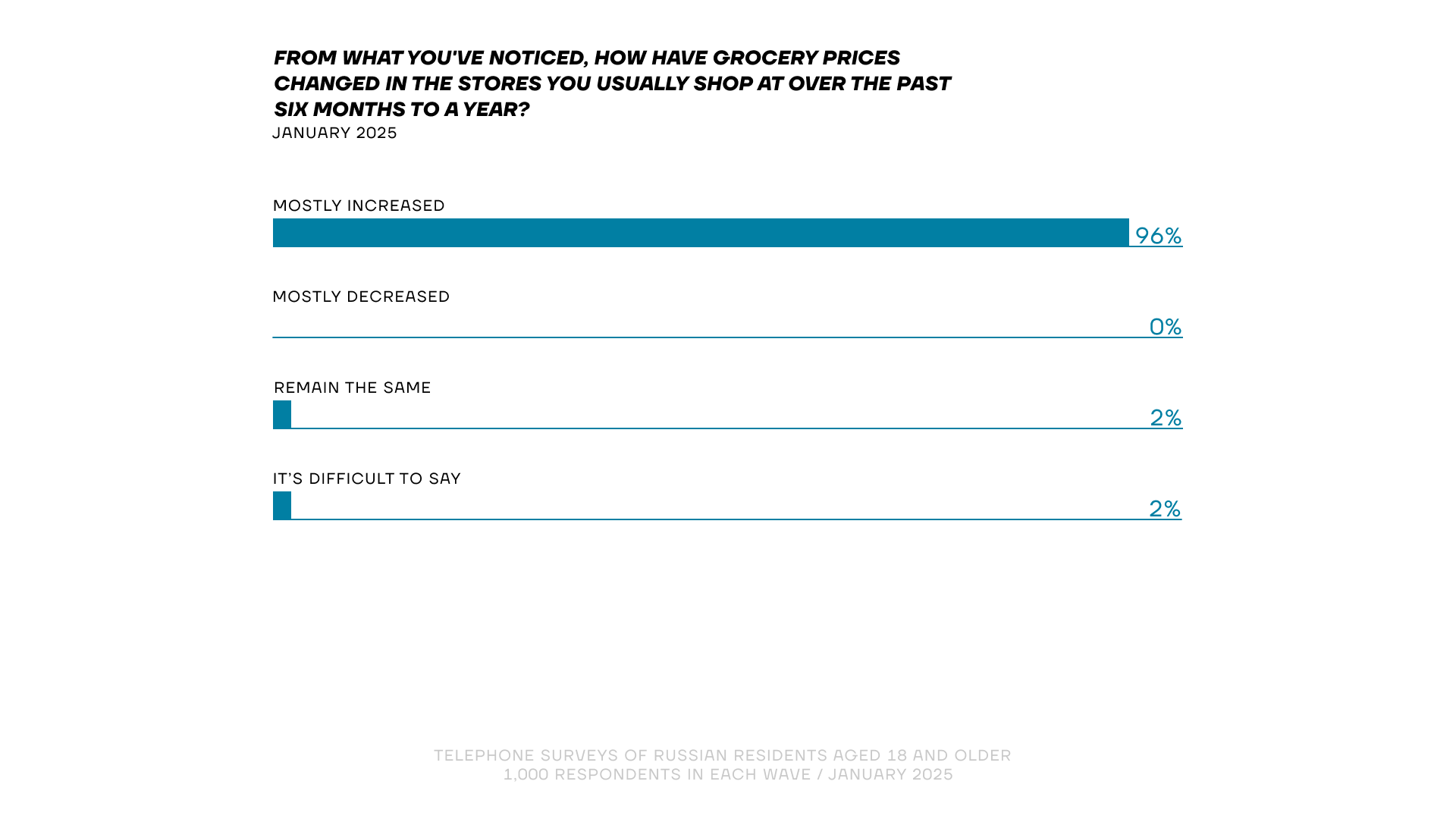

There’s no surprise when it comes to inflation—96% of people say they’ve noticed it. Only 2% say they’re unsure—likely those who don’t pay attention to prices at the grocery store. This issue has created near-total consensus across Russian society, and that consensus is having serious and even dangerous consequences.

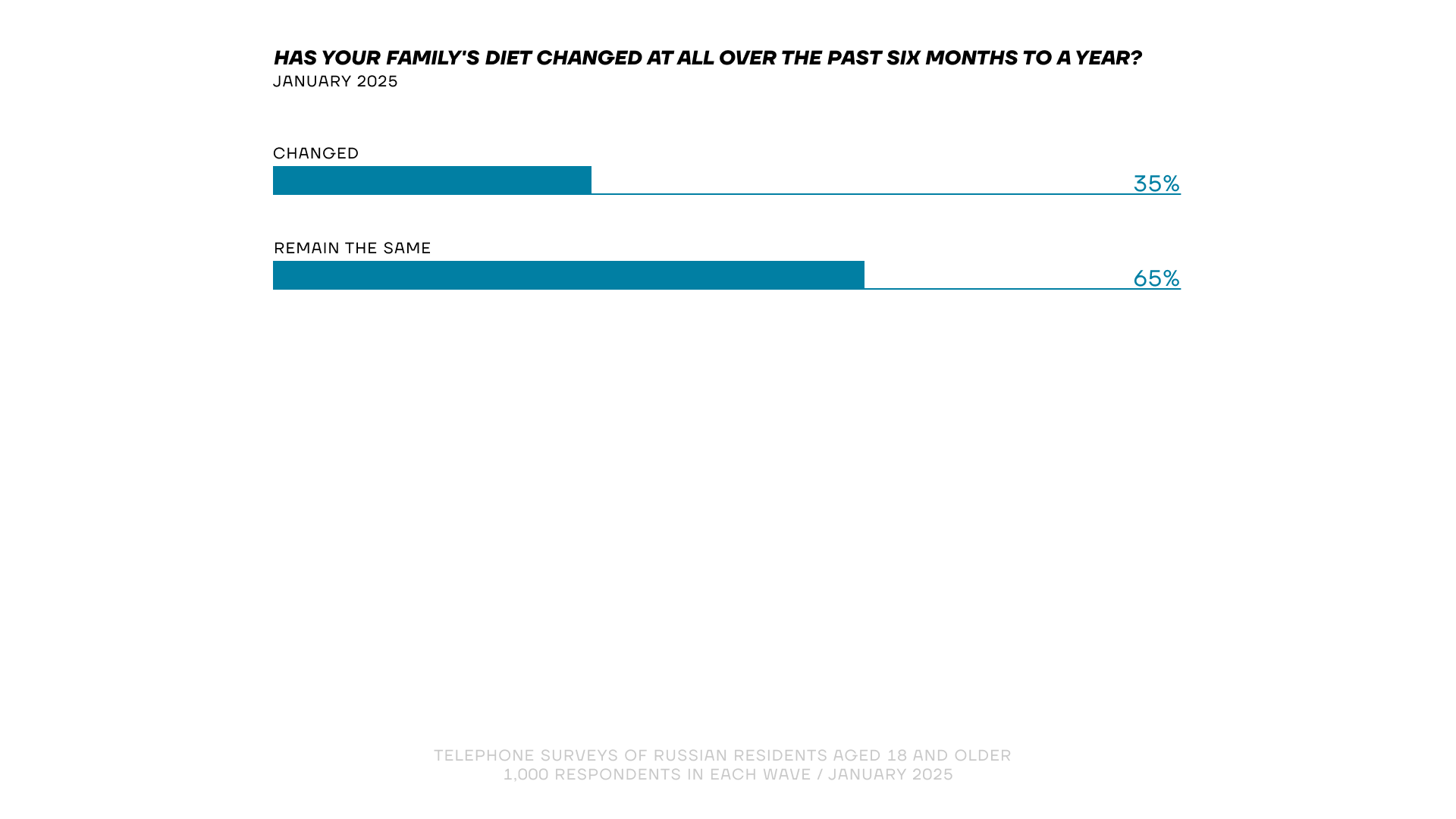

More than a third of Russians—35%—say they’ve had to change what their families eat because of inflation. This isn’t just poverty. It’s outright hardship—when people can’t afford the basic food they’re used to.

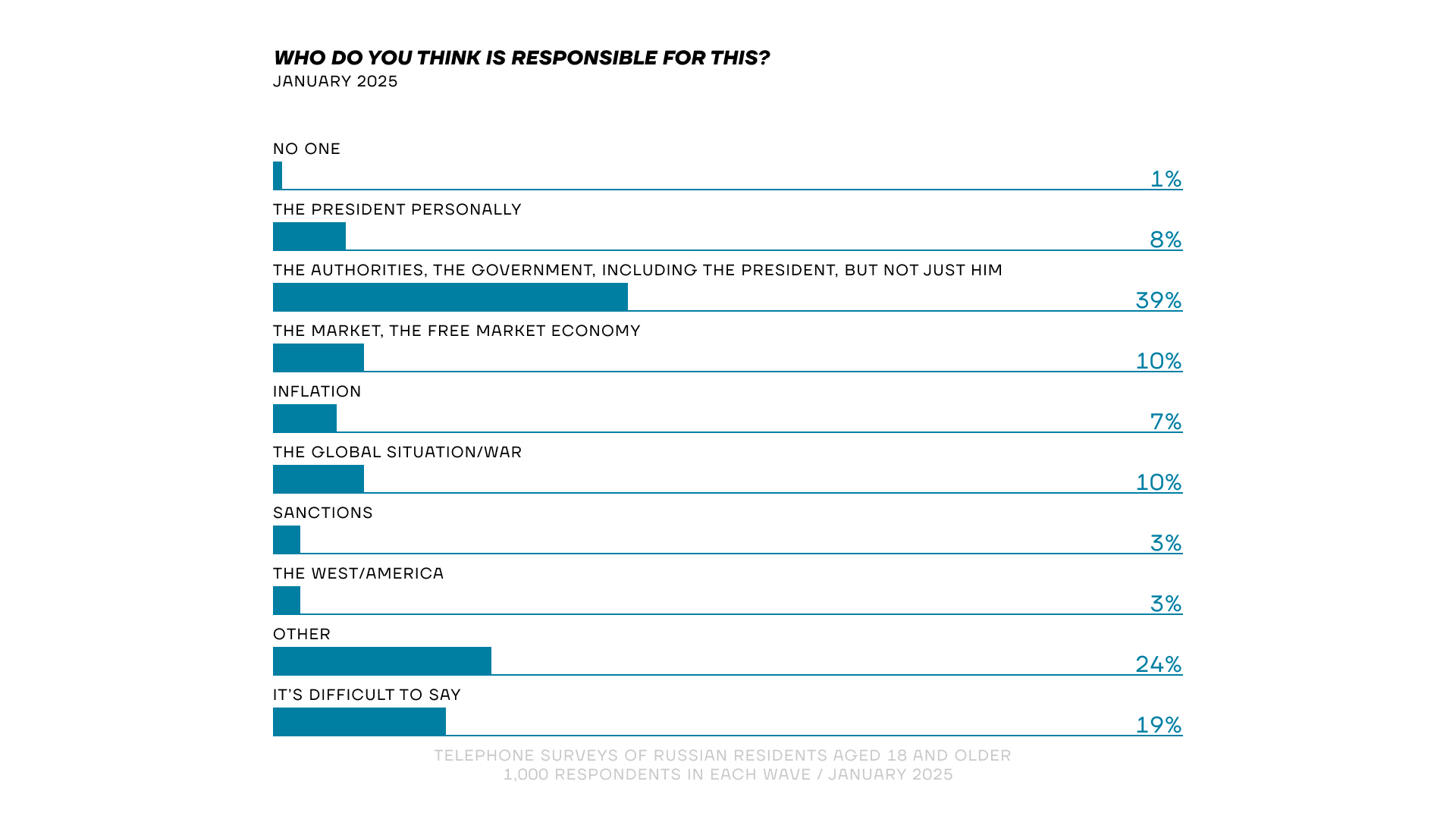

We then asked those affected by this: who do you blame?

The answer was clear—and it wasn’t Trump. 39% blamed "the authorities"—the government, the Kremlin, Putin, and his officials. Another 10% pointed to the war itself (and we all know who started that). Another 10% blamed the free market and the economy. 8% blamed Putin personally. And for comparison, only 3% blamed the U.S. sanctions.

In other words, as economic difficulties pile up, the effect of propaganda is fading away. When the fridge is empty, people stop listening to Vladimir Solovyov and his studio guests telling them it’s all America’s fault. Instead, more and more questions are being directed at the authorities, at Putin himself, and at the war he launched.

We felt it was important to share these outcomes with you. Thank you for supporting FBK.